High above the Douro, in the centre of medieval Porto, raises the cathedral, reminescent of a castle. Approaching from the narrow streets of the old city, you fist see her towers raising above the ramp to the place in front of the cathedral.

This place with its huge pillory looks ancient, but was created only in the 1940ies, when the Salazar regime wanted the cathedral to look more monumental. Before the creation of this place, this are was also dominated by old houses and narrow streets as the rest of the old city.

Since the invasions of visigoths ans suebes in the 6th century, Porto was a bishop’s see. In 711 Porto was conquered by the moors like the rest of what is now Portugal. Only in 1092 it fell under christian reign again. From here, Dom Afonso Henriques started the reconquista of the country. In 1110 bishop Hugo started to build the cathedral in Porto. The works finished in the 13th century, but the cathedral was continously extended and changed in the next centuries, so that the romanesc cathedral is now equipped with baroque and manieristic features. The north façade is extended by a baroque loggia, built by Nicolau Nasoni in the early 18th century. The main portal of the cathedral was rebuild in 1772.

When entering the cathedral one passes two stoups made end of the 17th century in pink marble. The central nave of the cathedral is clearly romanesc, having an impressive barrel vault. The apsis houses a gold plated altar from the 18th century, a masterpiece of joaninic baroque. The frescos at the apsis were created by Nicolau Nasoni. Left and right of the altar are two figures of Maria. Left the Nossa Senhora da Vendoma, who was declared patron saint of the city in 1984; right the Nossa Senhora da Silva. The name Nossa Senhora da Vendoma (our Lady of Vendome) can be traced to the times of the reconquista, when Porto was recovered from the Moores by basque troops from the city of Vendome. About the Nossa Senhora da Silva (our Lady of the woods) the story is told, that masons found the statue in a forest when they were carving the stones for the cathedral.

The transepts house two altars for the previous patron saints of Porto. On the right, St. Vincent, on the left the armenian Martyr St. Pantaleão. The mortal remains of St. Pantaleão were brought to Porto in 1453 and are buried in the cathedral beneath the altar.

In the left transept you can also find the chapel of the holy sacrament, whose altar is one of the most impressive works of portuguese goldsmiths. The altar is made completely out of embossed silver and was completed over three centuries. Work was started in 1632 by José Rodrigues Reixeira and only finished in the 19th century. During the napoleonic invasions at the beginning of the 19th century the city feared that the french troops would dismantle and steel the precious altar. A local legend (which is written in every guide book and also told by all tourist guides) says that a sacristan used lime to paint the altar white and thus managed to save the silver.

Unfortunately the historical records spoil this nice story: during the french invasions Porto was administered by a civil governor, Pedro de Mello Breyner. This Pedro Breiner negotiated with the french troops to save the alter and offered the same amount in silver to the french troops, if they left the alter untouched. The negotiations took a long time and never came to an end, as Arthur Wellesley, the Earl of Wellington, and his troops entered Porto from south and drove the french army back. The altar thus was saved and the silver did not be paid.

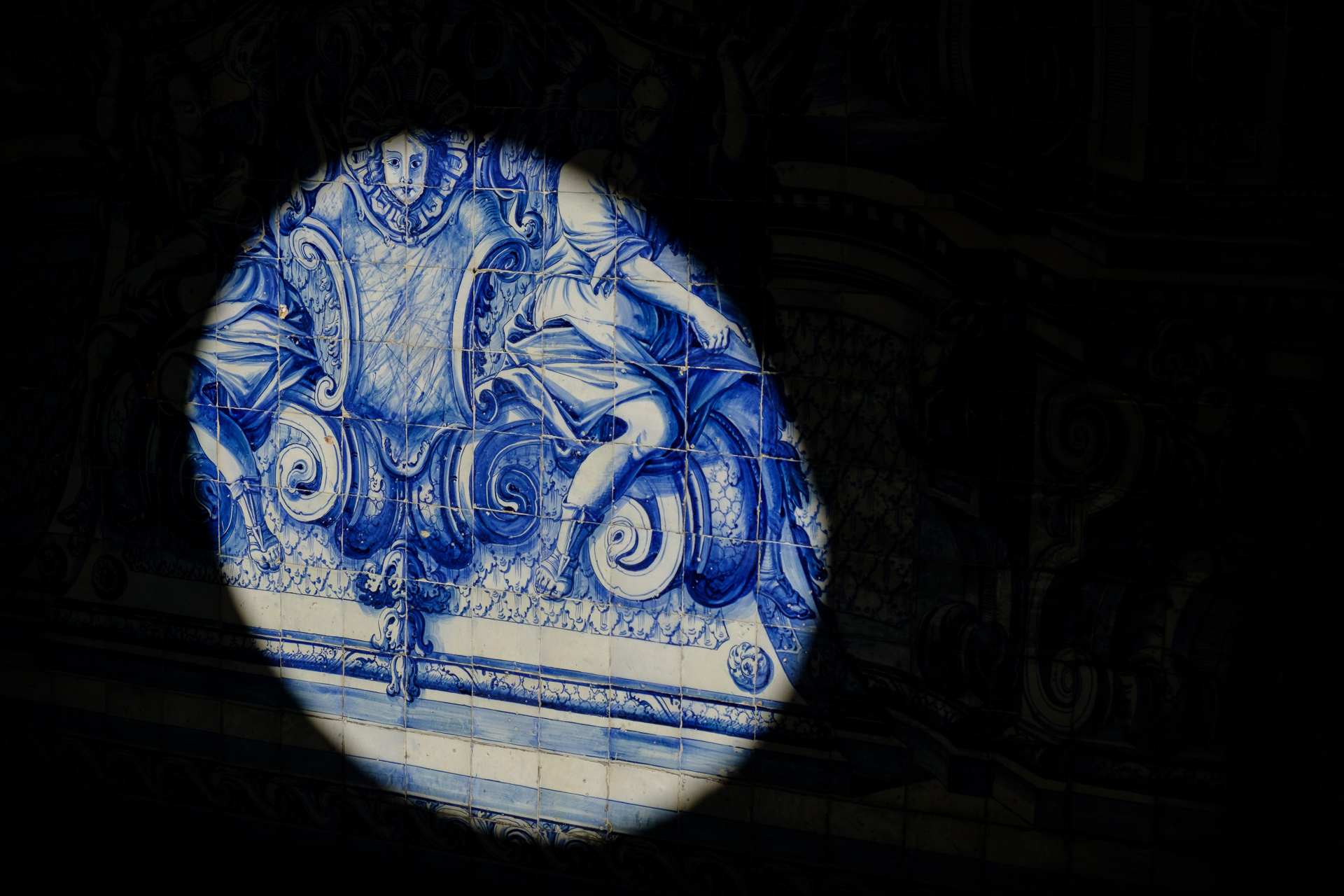

At the south side of the cathedral a gothic cloister is attached (where you need to pay a ticket for the cloister and the cathedral’s museum). The cloister is decorated with Azulejos, who were painted by Valentim de Almeida between 1729 and 1732. The tiles depict the life of Maria and scenes from Ovid’s metamorphosis.

Here one can find also one of the most beautiful works in the cathedral, which is missed by most. In a chapel at the south end of the capitular house, one of the most impressive mediaval sarcophagi in portugal is located. Resting on four lions you’ll find the sarcophagus of João Gordo, Knight of the order of Malta and former treasurer of the house of Dom Dinis. He died on December, 10th, 1333 and for him this chapel was build as an annex to the cathedral. Historically this is an interesting situation, as normally such a sarcophagus and a chapel was reserved to royality or the clerus, not an albeit rich but else normal citizen. This shows the high position and rank that João Gordo must have had in society at that time.

The long side of the sarcophagus displays the last supper. The foot end depicts the calvary and christ’s crucifiction, the head end the coronation of Maria. The depiction of the last supper is somewhat curious, as the figure to the right of Jesus seems to be hold headlock by Jesus and some kind of cloth strip is coming out of his mouth. I haven’t found out what this should symbolize…

The capitular house gives access to the first floow and a terasse above the cloister. In the staircase, which was desigend by Nicolau Nasoni, you’ll encounter an old church bell. This bell was placed 1697 in the southern tower of the cathedral and was used to signal the dusk-to-dawn curfew. In medieval times there was a strong rule: after the bell had chimed three times, all light in the houses had to be extinguished and everybody who was found on the streets was arrested immedeately. The bell was first located in the cities gates, but moved to the cathedral in 1583. In 1697 lightning struck the cathedral and damaged the old bell. The bell which is now found in this staircase was the replacement of the damaged bell. It was placed in the southern tower. 1847 lightning struck again, but there were little damages this time.

In the first floor you can walk on a veranda on top of the cloister, whose walls are also decorated with Azulejos. Back through the capitular house you enter the museum of the cathedral. It houses some nice pieces of sacral art as well as some historic rooms used by the clerus in former times. The museum is not very large, but worth a visit.